Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

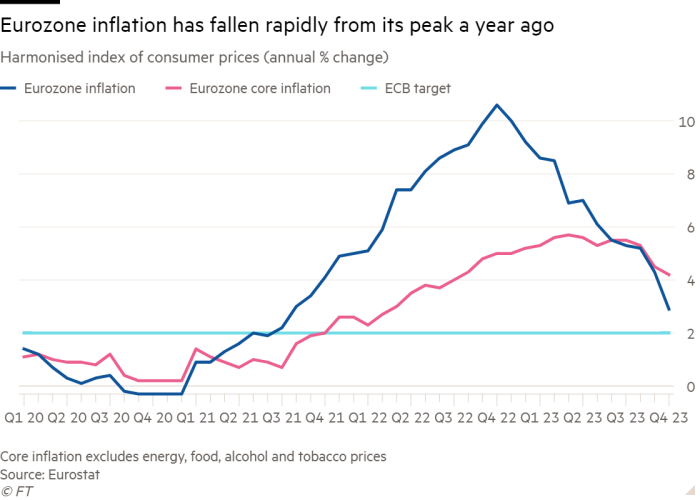

Eurozone inflation has fallen more than economists expected to 2.9 per cent in October, the slowest annual growth in consumer prices since July 2021, after the bloc’s economy started to shrink in the third quarter.

The big reduction from 4.3 per cent in September was mainly a result of falling energy prices and a drop in food inflation, according to Eurostat, the EU statistics arm. Economists polled by Reuters had expected eurozone inflation to be 3.1 per cent in October.

The sharp slowdown in prices reflected weaker activity in the eurozone economy, which Eurostat said shrank 0.1 per cent in the three months to September, undershooting economists’ forecasts, after contractions in Germany, Ireland and Austria offset growth in Spain and France.

The figures add to evidence of stagnation in the eurozone economy, which has barely grown in the past year as consumers and businesses have faced rising borrowing costs, weaker global trade and the biggest surge in the cost of living for a generation.

The drop in underlying inflation adds to expectations that the European Central Bank will not raise interest rates further, after it held its benchmark deposit rate steady at 4 per cent last week, ending its unprecedented series of 10 consecutive increases.

However, economists said the disinflation process was likely to slow as the Israel-Hamas war pushes up energy prices and the base effect of comparing energy prices with last year’s high levels diminishes. Inflation ranged from 7.8 per cent in Slovakia to minus 1.7 per cent in Belgium.

“Looking ahead, inflation is unlikely to keep falling this quickly,” said Jack Allen-Reynolds, an economist at consultants Capital Economics, adding that “energy inflation will probably pick up a little in the next few months” and EU survey data pointed to a stabilisation in services inflation.

Core inflation, which excludes energy and food and is closely watched by the European Central Bank as a gauge of underlying price pressures, fell in line with expectations to 4.2 per cent, down from 4.5 per cent the previous month. Services inflation fell 0.1 percentage points to 4.6 per cent.

But ECB president Christine Lagarde said last week that wage growth was “critically important to determine the inflation outlook”. She pointed out that details on the next round of collective wage bargaining agreements with unions would only come “way into 2024” — suggesting the ECB would wait until then before deciding if it could start cutting borrowing costs.

“The ECB needs to see wage inflation slowing and this could take a further six months,” said Mark Wall, chief European economist at German lender Deutsche Bank.

Eurozone energy prices fell 11.1 per cent from a year earlier, while the price of food, alcohol and tobacco rose 7.5 per cent, compared with 8.8 per cent the previous month. The month-on-month rate of inflation was 0.1 per cent.

Austria’s economy contracted 0.6 per cent in the third quarter, while Irish output fell 1.8 per cent. Spain grew 0.3 per cent, France 0.1 per cent and Italy stagnated. Figures released on Monday confirmed Germany’s place as one of the world’s weakest major economies after its gross domestic product shrank 0.1 per cent.

Compared with a year earlier, output in the economies of the 20 countries that share the euro was 0.1 per cent higher in the third quarter. That contrasts with a rapid expansion of the US economy, where annualised third-quarter growth was reported at 4.9 per cent last week.

Third-quarter eurozone GDP was weaker than the zero growth forecast by economists in a poll by Reuters. Eurostat said the bloc’s slight contraction was also a reversal from upwardly revised growth of 0.2 per cent in the previous quarter.

“Momentum going into the fourth quarter remains exceptionally weak, weighed down by tight financial conditions,” said Rory Fennessy, an economist at consultants Oxford Economics. “The eurozone economy is set for a period of economic stagnation, with growth only returning once real income growth turns sufficiently positive.”