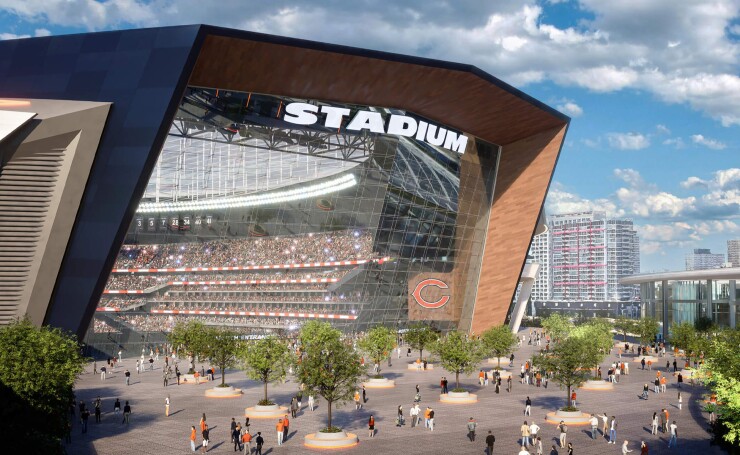

The National Football League’s Chicago Bears last week unveiled sweeping plans for a new domed lakefront stadium in the city that they say would cost about $4.7 billion total and involve $900 million in new bond financing through the Illinois Sports Facilities Authority.

The plan has vocal backing from Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, but got a more skeptical response from state government officials, who have a big say in the ISFA.

According to a presentation by the team’s chief operating officer and executive vice president of stadium development, Karen Murphy, that total price tag includes $3.225 billion for the stadium itself; $325 million for transportation, roadways and utilities; $510 million for parking and bus depot expansions and new parks; and $665 million for retail and public attractions.

Chicago Bears

The crux of the Bears’ debt proposal is a scoop-and-toss refinancing, or a move to delay debt service payments, on $430 million of roughly $600 million of outstanding stadium debt by selling new bonds.

According to Murphy’s presentation, ISFA, a state entity, would restructure existing stadium debt, extending those bonds 40 years, thus creating capacity for new debt this year.

The ISFA board is a mix of gubernatorial and city appointees, all of whom are confirmed by the state Senate. It was created to fund and operate the Chicago White Sox baseball stadium that opened in 1991 and finance massive 2003 renovations to Soldier Field, where the Bears play now.

ISFA CEO Frank Bilecki said by email that the refunding of a portion of the existing stadium debt would cost $1.34 billion over its term. The new $900 million of debt would cost $3.5 billion over its term. So the total costs of the Bears’ debt plans would come to at least $4.84 billion.

“ISFA looks forward to further discussions with the Bears to review further details, including their payment schedules, interest rates, growth rates and more,” Bilecki said. “As plans are being discussed, it is with the lens of what is the most financially responsible plan for taxpayers that ISFA will be using to review financial models.”

The McCaskey family, which owns the Bears, has said it will contribute just over $2 billion in private investment, and the team will also take out a $300 million loan from the NFL.

According to Murphy, the new bonds would be backed by the city’s 2% hotel tax, and the Bears want to create a liquidity reserve fund of $150 to $160 million to cover any hotel tax shortfall. The team is projecting the net new bond proceeds will generate over $1 billion, assuming the historical growth rate of the hotel tax endures.

“Hotel taxes are relatively volatile, and they definitely swing with the economy,” Chicago’s Chief Financial Officer Jill Jaworski said at the Bears’ Wednesday press conference. “One of the things that got us comfortable [with the Bears’ proposal]… is that they’re assuming a lower rate of growth… that is more reasonable” than previous projections that didn’t take into account a pandemic or a recession.

“Under the current debt service that ISFA has for remaining debt, the debt is going to spike up pretty significantly between now and 2032 when it expires,” Jaworski added. “We would expect without a refinancing that that would hit the city budget every year in an increasing amount. So refinancing that and looking at the longer structure… we think that insulates us more.”

Chicago has a history of

Richard M. Daley, mayor from 1989-2011, relied on the tactic, as did successor Rahm Emanuel, who ultimately managed to wean the city off general obligation scoop-and-toss toward the end of his administration in 2019. The administration of his successor, Lori Lightfoot, went on to

Civic Federation President Joe Ferguson said it’s early yet to say “how this will land,” but added: “The Civic Federation has long, strongly opposed scoop and toss financing mechanisms. The city of Chicago made the correct policy decision to eliminate this practice; it is not sound policy to revive it. Over time, these arrangements substantially increase long-term costs.”

He noted that scoop-and-toss refinancings “often tend to lead to even more restructurings” to balance future budgets, multiplying the long-term costs.

According to Bilecki, by 2025 ISFA will have already paid $371.8 million for the White Sox’ Guaranteed Rate Field and $614.9 million for Soldier Field. He said the Bears assume ISFA will go to market sometime in 2025.

The issuer received an upgrade to investment-grade BBB from speculative-grade BB-plus from Fitch Ratings

Under the legal structure backing the bonds, the state “advances” up to 60% of a 5% statewide hotel tax to the ISFA a few months ahead of the annual debt payment. After making the debt payment, the agency must repay most of the state advance, using a local 2% tax on Chicago hotels as well as $5 million annual subsidies from the state and from the city.

If Chicago hotel revenues fall short, as they did during the pandemic, the state is made whole with income tax revenues that would otherwise go to the city of Chicago, according to Fitch. So the city is ultimately on the hook.

Ferguson said that from the Civic Federation’s perspective, several things are concerning about last week’s rollout. One is “it was stadium and Bears-centric, rather than economic development and community benefit-centered.” Another is that it failed to take account of all revenue and expense components.

“Infrastructure was acknowledged, but as a side note,” he said. “The financial relationship between the Park District and Bears was unmentioned.” And there were other omissions, such as the financial consequences of the proposed refinancing, Ferguson said.

The Chicago Park District owns Soldier Field and the land on which the new stadium would be built. The Bears reportedly want to keep all the revenue from events such as concerts the new stadium would host.

Jaworski was unavailable for comment by press time. At the press conference Wednesday, Mayor Brandon Johnson stressed that the proposal involves no new taxes on residents of Chicago.

“My team upheld my clear criteria,” he said. “We required real private investment, real public use and real economic participation for the entire city. And today’s announcement delivers on all three.”

“We expect [questions]. We embrace that,” Bears President and CEO Kevin Warren said at the event. “But I’m confident that we can come together to show future generations that people can work together… We want to build a recreational and cultural campus… We tried to be fiscally responsible about building this stadium.”

At an unrelated

“From my perspective, the deal that was presented didn’t take into account that taxpayers really aren’t going to do well under that proposal,” he said. “It seems to me that the team owner, who benefits most, ought to be the principal provider of the capital – and when I say principal, I mean the vast majority of it.”

Pritzker Deputy Chief of Staff for Communications Jordan Abudayyeh said any state funding would have to come with “a real, tangible benefit for taxpayers,” adding, “As economists have pointed out, past stadium deals have not lived up to the promises they have made when it comes to the economic benefit for taxpayers.”

Two days after the Bears’ high-profile press conference, a panel that included state and local lawmakers gathered at the Union League Club of Chicago to discuss who wins when sports teams set out to build a new stadium.

Among the suggestions floated by panelists were a binding referendum and an equity stake for the state of Illinois in the team.

“If we’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars in subsidies… what does it look like to change the paradigm and say that that investment should come with some equity?” said state Rep. Kam Buckner, D-Chicago. “I would love to at least broach the conversation about what 10% ownership of the Chicago Bears looks like for the state of Illinois, and earmark those funds going directly to our pension debt. Let’s get creative.”

Buckner said public financing for sports stadiums was once “unheard of” in America, and said that teams now often put public officials in a tough spot.

“We’ve seen teams really use the threat of leaving a location to make people do things like public subsidies,” he said. “But we’re also now starting to see pushback. You see what happened in Kansas City, where they put a referendum on the ballot where, even after winning the Super Bowl, folks who lived in the town said that

Jennifer Shea

Buckner blamed the NFL and Major League Baseball.

Teams like the Bears and the White Sox, who have proposed their own new stadium development to replace their current subsidized Chicago venue, Buckner said, “are playing by the rules of engagement… The NFL and the MLB have created this untenable sweepstakes of, who can get a new stadium the quickest? … We need to put more pressure on the NFL and the MLB to stop doing that.”

Regarding the Bears’ plans, 11th Ward Alderman Nicole Lee was noncommittal, saying “the devil is absolutely in the details” on any stadium deal, but also sounding a note of caution.

“I don’t necessarily feel good about the fact that we’re talking about building new stadiums when we have two perfectly good stadiums that we haven’t quite finished paying for yet,” she said. “All of these sports teams, they are for-profit companies. Their goal is to make money for their teams… Having conversations about subsidies for sports stadiums feels like quite the luxury at this point.”

Dr. Geoffrey J.D. Hewings, director emeritus of the Regional Economics Applications Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, issued the most scathing appraisal of the afternoon.

“Why should the public end up paying anything towards the costs of these stadiums?” he said. “Why don’t they go to the market and get loans for the rest of it, and then pay it off from all the additional profits they plan to make from the stadium? Why should we end up having to underwrite them, when we still have $600 million outstanding that still hasn’t been paid off? I think there’s a really serious equity issue here… It’s a misallocation of public funds.”

Hewings noted that any public subsidy for the Bears would most directly benefit some 70,000 season ticket holders, comparing that to the 74 million people who used O’Hare last year: “Does the sports team provide that sort of economic engine?” he added. “I think the answer to that is no, it does not.”

At the press conference, The Bears’ Warren said the team, which until recently was pursuing a new venue 27 miles away in suburban Arlington Heights, envisions a year-round hub of activity, with 14 acres of athletic fields and recreational parks, ice skating in winter, farmer’s markets in spring and summer, graduations, concerts and even Super Bowl and World Cup games.

And the Bears cite an

But the Bears are also calling on lawmakers to act immediately, with little time for deliberation, let alone for the advisory or non-binding referendum that former Gov. Pat Quinn has advocated.

“Now is the time to act. There is a significant cost to waiting… The cost to maintain this building gets more and more expensive each year,” the Bears’ Murphy said Wednesday, arguing that the funding gap will increase by over $150 million for each year waited.

“The problem is, we’re [making decisions] on the basis of emotion,” Hewings said. “I think we’re [being] very disingenuous to the public by assuming that they’re not sophisticated enough to make informed decisions.”